If you prefer to read the preface offline, feel free to download the pdf here (650 KB)

We called our home the Blue Ghetto. Each spring it accreted along both sides of a dirt road you could walk the length of in two minutes. Our scrap of road collided at one end with the backside of Three Rivers Lodge, the rustic resort that largely comprised the town of Lowell, Idaho. The other end was swallowed by a wall of dense, dark, dripping green: the Clearwater National Forest. Alongside, screened from view by willow and syringa, ran the Lochsa (pronounced LOCK-saw). This mountain river swells each spring with snowmelt and rainfall, pounds through dozens of powerful rapids in a handful of miles, and then, just downstream of the lodge, folds with deceptive peace into an even better known mountain river, the Selway.

The denizens of the Blue Ghetto were whitewater raft guides, many of us career guides, as we liked to point out to one another. We were not working summer jobs until something better came along. We were living the life. We might not own much, but neither were we owned. We might not be eligible for credit cards—people without permanent addresses tend not to be—but credit cards looked like bad magic, the real-life lamp with the prankster genie inside.

So the ‘ghetto’ in Blue Ghetto was ironic. We were proud of our poverty and what it bought.

The blue was literal. On the Lochsa in the spring it rains and rains. So we strung cheap blue plastic tarps over our campsites like so many miniature blue skies. The twilight shadows that pooled beneath turned even our faces blue.

It was a glorious mess. Our cheek-by-jowl camps were mud-sticky and puddle-mined, encircled by shallow trenches we dug to divert water around our tents and cooking areas. Some of us slept on salvaged wooden pallets, others in trucks backed up to the ubiquitous tarps. We built shelves and tables out of waste lumber and driftwood. All of it was festooned with boating gear that seldom dried.

As you might expect, our tiny enclave was well endowed with colorful characters. There was Dave, who was in his mid-20s but had yet to own a car. In fact he didn’t know how to drive. He hitchhiked to every destination he couldn’t reach by bicycle, including the Lochsa and, somehow or another, Tibet.

There was Lonnie, who had a Master’s degree in something I could never remember, although I occasionally heard him mention it to curious guests. An accomplished storyteller, Lonnie liked to kick off his sandals before beginning a tale. Then he’d scuff his feet into the grass or sand as though cleaning a battery terminal. Hooked to his source, still silent, he’d fold his body into an angular origami squat and swivel his long neck until he had captured every eye. Then he’d begin.

There was Carol, in her late 20s with thick dark hair that she kept in elaborate cornrows and ropy braids. She chewed tobacco and sang like a whiskey-bent angel. Her laugh was easy and raucous. You could hear it clear across the river. Despite the tobacco-flecked teeth, weathered skin and bulging biceps, the impression she left in her wake was that a mischievous child had just skipped by.

We played a drinking game there at Three Rivers. Orders from above said guests were not to know about it or, better yet, that we were not to play it. But orders from above felt optional at ground level, and the game thrived.

It went like this: At day’s end, any guide who had flipped a boat in the rapids owed the other guides a 12-pack of beer, deliverable upon our return to Three Rivers. But if a guide dumptrucked, in other words if his guests went swimming but the raft remained upright and the guide himself managed to stay onboard, the other guides owed him a 12-pack.

It was of course the dumptruck bit our boss did not want guests to hear about. He said it sounded as though we liked to see guests in the water. He had a point, so we humored him enough to stop chortling about free beer after such ‘carnage’ occurred. But we didn’t stop playing. We called a guide’s post-flip walk to the resort store ‘the walk of shame.’ We did not stop chortling about that.

Rafting company clientele run rivers for lots of reasons, but our guests, the people who had picked the Lochsa, wanted a wild ride. On the ride upstream to our launch, we passed photo albums around the bus, taken by the company that shot souvenir whitewater pictures for us. We told the guests they’d be starring in that afternoon’s slideshow. The images in the albums were of rafts twisting into the air as though propelled by land mines; rafts dumping their human contents into roiling chaos; rafts plowing so hard into boulders that they folded themselves into bulbous, 15 foot-long L shapes. Carnage pays, we liked to say. And on the Lochsa it did.

But this book is not about the Blue Ghetto or the Lochsa. Nor is it about me, except indirectly. The reason for describing all this—the Ghetto, those guides—is because if you stand there with me, on that muddy dirt road beside that lovely wild river, you’ll see how we might have felt ourselves special, exempt in some way from rules that bind other lives. Not that we would say so and not that we thought ourselves invincible. That’s different. Occasionally a guide blew out a knee in a violent paddleboat toss or split a lip on the back of a guest’s helmet. You expected that.

But picture it. We threw ourselves at that wild river every day and most days it tossed us all harmlessly skyward like well-loved children. After a while that does something to you.

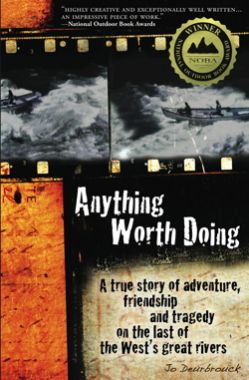

What this book is about is a subculture that still, in memory, charms me. It’s about two men named Clancy Reece and Jon Barker, two of the most fascinating raft guides that subculture produced. It’s about freedom, adventure, death, and those rare people who, like Clancy and Jon, never unchoose simple lives defined by such harsh and lovely bargains.

I remember exactly when I began to unchoose that life, or at least that’s what I thought was happening at the time. Looking back, I realize I’d never completely accepted its tradeoffs. I was standing in a phone booth outside of Three Rivers Lodge, staring blankly at the Lochsa while a stranger’s voice explained why my friend Jim Yetter hadn’t rejoined me at Three Rivers as we’d planned.

The next day I received a letter. J. Yetter, Banks, Idaho, said the envelope’s upper left corner. I watched the hand which held the envelope begin to shake. Because what the voice on the phone the previous day had told me was that Jim was dead.

Long-limbed, blond and beautiful, Jim had been a guide for another Lochsa company. He had taken a boatman’s holiday to kayak the infamous North Fork of the Payette River. There he had drowned.

This was perhaps my second summer as a guide. As an inexperienced oarsman, I worked family trips on moderate, class III rivers. Class III whitewater can look intimidating to the uninitiated, but its obstacles require no great skill to avoid. The waves can be large but they are predictable. Class III is where whitewater guides cut their teeth.

I had been sent to the Lochsa to see what serious paddle boating looked like and, presumably, so the boss could see if I had class IV-V potential. The Lochsa exhilarated and intimidated me. It was the real thing, a whitewater river that required skill and attention and even a bit of luck. What I had heard about the class V North Fork, where Jim had gone to play, was that it was tougher even than the Lochsa.

In his letter, Jim had written that he had broken his paddle that day in a tough rapid. In water so churned it seemed mostly air, he’d been forced to wet exit from his kayak and swim for shore through a mass of wave-pounded boulders. He didn’t know how he had escaped injury. The next day, he wrote, if he could find someone willing to boat it with him, he would try the section boaters call the Middle Five. I didn’t know it then, but the Middle Five is the most difficult, dangerous stretch of the North Fork. Plenty of North Fork kayakers won’t run it.

Jim did find a paddling partner for the Middle Five. Everything went well with their run until the last rapid, and what went wrong there nobody will ever know because the other paddler didn’t see it. What he saw when he turned around at the bottom of the rapid was Jim’s kayak completing the run upside down. When Jim didn’t exit the kayak or roll upright after what seemed more than enough time, the guy paddled over and spun the boat up. Empty cockpit.

After a frantic search the paddler located Jim, probably alive at first, but only in a technical sense because Jim Yetter would never get the chance to breathe again. He was wedged under a submerged log three feet beneath the surface. The way the story came down the grapevine, the guy could reach Jim with his fingertips but couldn’t budge him. He couldn’t budge the log either. At some point he scrambled up onto the highway for help, which is the same as saying he surrendered to inevitability. Every whitewater boater knows the rule: one minute to unconsciousness, five to almost certain brain damage, then death.

It was evening before the body was retrieved. By then Jim’s letter was on its way to me.

There is a part of that letter I will never forget. Among the talk of broken paddles and nasty swims, Jim had written this: “I’m having the time of my life.”

That autumn I drove to the North Fork, found the rapid he had died in, and climbed down the steep bank to the water’s edge. I opened the letter and reread that line. By now I could find it in an instant, below the second worn fold on page two. Then I slipped the letter, which had grown too precious to carry, into a crack between two rocks. Standing there, I promised myself that someday I too would kayak the North Fork.

I had never kayaked a class V river. Nor had I thought much about whether I cared to, except that it was what good boaters did and I intended one day to be good.

I did eventually keep that promise and run the North Fork. By then I was a full-fledged Lochsa guide as Jim had been. Up or off, as climbers say, and by that time I’d been guiding for some five years. Few women worked the Lochsa in my day, but I’d studied and practiced that style of river, then worn my boss down to a definite maybe, then demonstrated the necessary skill.

I did my job on the Lochsa competently. I had no more than my share of swimmers, several perfectly glorious dumptrucks, and no guest injuries more severe than a bloodied nose. But I often guided lightheaded with fear. Some nights I dreamed a swimmer from my raft had been sucked under a log and no matter how hard I tried I could only brush his inert form with my fingertips.

Evenings after work, a few of the guides would load their kayaks and drive back up to a rapid called Pipeline, the heart of which is a powerful surf wave. I seldom went, although I envied whatever in them drew them back to a river which had released them for the day. Or what wasn’t in them. Because I assumed without asking that unlike me, they felt no fear.

Then one day a young man tumbled from my paddle boat into a big ‘hydraulic’ below a rock. Boaters have many names for such hydraulics but the most common is ‘hole’ because of the way these river features tend to yank anything at the surface down. Strong holes also cycle currents back up and then roll them under again, so the experience of swimming a hole is sometimes described as getting ‘washing machined.’

The whole thing happened, as crises do when you have mentally rehearsed them, within a curious stretching of time. The raft dropped over the submerged boulder that created the hole, caught, and then began to buck. Five of my paddlers tumbled onto the floor. The sixth began to tip toward the most powerful part of the hole.

I had what seemed years to decide that this soon-to-be swimmer was, for the moment, more important than my pummeled raft or the paddlers jumbled inside. I slammed my paddle blade under a thwart and lunged to hook the shoulder of his lifejacket. My hand wrapped solidly around fabric.

It was a nasty hole. If I had missed my grab he’d have been yanked under like a fishing bobber. He’d have been released—keeper holes exist but they are rare and this was not one of them—but not before he completed a scary and perhaps painful swim. That solid handful of fabric said he’d be back in the boat before he could register that he was wet.

But that’s not what happened.

My swimmer was yanked under so hard that I was pulled half out of the raft after him, my arm submerged to the shoulder. His sunny yellow helmet was an indistinct greenish blob in the aerated mess of the hole. What held us both was my leg, which I had jammed into the gap between the thwart and the boat’s inflated floor so hard I would later find bruises.

I yelled my paddlers back to their positions. In moments they began to dig hard at the boiling water. From my awkward position I pulled for perhaps 15 seconds but I might as well have been trying to haul a tree from the ground.

Holes tend to hold most fiercely to objects at the surface because that’s where the currents are in greatest conflict—which meant that although my raft was caught, my swimmer didn’t have to be. I was holding him in that hole. I began, silently, to count. I hated the thought, but at ten I planned to let go and give him to the river while he still had the strength to swim. The hole would pull him down, but it was weakest in its depths. He’d be released into downstream current and then his lifejacket would haul him back to the surface and he’d be rescued by the rafts waiting below.

I was on four when the paddlers won us free. An instant later the young man popped to the surface. I hauled him from the water and dumped him onto the floor of the raft where he lay, sans pants and one shoe, gasping and coughing. His eyes flew open and he stared at me, in the grip of an emotion I had never before seen but instantly recognized: mortal terror.

That look rattled me, but when I told the story I made the whole thing into a joke, on him for thinking that losing his pants comprised a brush with death, and on me for allowing my boat to run one of the biggest holes in the river in the first place.

I was still special that day, one of the charmed, if just barely. Then in June of 1996, word ripped through the guiding community that another of ours was dead. Then we heard he’d been one of the old timers, a real dinosaur.

Word was that the guy had been on a boatman’s holiday as well, only his was a high water run down Idaho’s longest wilderness river, the Salmon. The Salmon is not normally a difficult river, but this was a booming high water year. On the Lochsa we’d been canceling trips for safety.

Extreme high water or not, the news didn’t make sense. Rivers are notorious for slamming the foolish ass over teakettle and even more notorious for giving the undeserving a pass. But although we all paid lip service to water’s caprice, none of us believed in our hearts that rivers killed the respectful, which we all said we were, and especially not the consummately skilled, which is what it meant to say the man was a dinosaur. Maybe we even thought the river might respect such an oarsman in return.

Then I heard the victim’s name: Clancy Reece. A dinosaur’s dinosaur. The guy who’d taught the people who had taught me. Their hero and mine. I had known him only to say hello to at boat ramps, but like everyone in Idaho rafting at the time, I knew the Bunyanesque stories. I knew—hell, everyone knew—that Clancy loved a challenge. People were saying that he and a lifelong friend, a serious adventure boater named Jon Barker, had been trying to set some kind of world record.

And someone said this: He must have been having the time of his life.

I guided for several more summers, but that day I realized there would be an end to it for me. I was not a career guide after all. I know now that there are very few career risk takers of any stripe. Most people hedge their bets.

Years later I went to hear a climber and extreme snowboarder named Stephen Koch. After his slideshow—full of edgy images of him flying down chutes steep as rainspouts, walled by ragged rock or empty air—an audience member asked why he took such risks. He’d been nearly killed in an avalanche on Wyoming’s Grand Teton. Despite injuries which included a broken back, he was snowboarding extreme terrain again within a year. Since then he’d attempted an alpine-style ascent of Everest, just he and a few friends traveling light and moving fast. That’s not how Everest is usually attempted. Because of the likelihood of mishap in that extreme elevation environment, Everest is nearly always approached siege-style, with a virtual army of backup personnel and gear. Yet despite those precautions the mountain still kills at least two climbers in a typical year. Unexpected storms have been known to wipe Everest hopefuls off the roof of the world by the handful. How could Koch say he valued his life, the audience member asked, if he took such risks with it?

By then I was pushing 40. Risk had become a complicated word, all tangled up with dreaming and doing, compromise and cost.

“I do not risk my life,” Stephen answered. “I take risks in order to live. I take risks because I love life, not because I don’t.”

Listening to the reaction of the crowd, which ranged from boisterous whistles of approval to dissatisfied silence, and feeling that entire range echo in me, I realized how badly I wanted to write about Clancy Reece. I wanted to write about lives balanced between freedom and risk, lives founded on what at the time seemed to me a fantasy—that childhood wouldn’t end, that the bill would never come due.

Most of all I wanted to know whether, if Clancy could have looked at the path of his life in hindsight, as I could, he would have—or could have—unchosen any of it.